They’re all globally admired, rooted in distinct communities, and each faces pressure from cheaper substitutes, shrinking artisan incomes, or fading intergenerational transfer of skills. Several are Geographical Indication (GI)–protected, which helps—but isn’t a silver bullet.

Mashru (Kutch & Patan, Gujarat)

What it is?

Mashru is a historic silk–cotton cloth with a glossy silk face and a cotton back. Its name comes from the Arabic mashrū‘—“permitted”—because it let Muslim men enjoy a silk look without silk touching the skin (a religious stricture in many traditions). Typical looks: narrow candy stripes, bold chevrons, or warp-ikat patterns.

How it’s made (in short)

Warp-faced satin (silk warp floats over cotton weft), then calendered/finished for sheen; some historical pieces use warp-ikat for the zigzag/chevron effects.

How to spot the real thing

- Flip the fabric: you should see/feel cotton on the back and silk on the face.

- Look for crisp warp stripes or precise warp-ikat; handloom pieces have subtle irregularities at selvedges.

What’s threatening it?

Mass-made “mashru look” polyester satins; fewer master weavers in Mandvi/Patan; low margins for intricate warp-ikat variants. Revival projects and designer collaborations help but production remains niche.

Who’s preserving it

Craft groups in Kachchh and museum documentation (e.g., Cleveland Museum’s mashru fragment) keep the knowledge visible; some Indian labels commission small runs to keep looms active.

What it is

A striking red-black-on-ivory embroidery practiced by the Toda pastoral community; locally called pukhoor. Both sides are so neatly worked that the cloth is reversible—traditionally worn as a shawl/cloak (often called puthukuli/poothkuli). It received GI protection; the certificate was formally presented to the community in June 2013.

How it’s made (in short)

Counted-thread, reverse needlework on an even-weave white cotton: artisans “count” warp and weft, stitching from the back so small loops build a raised, woven-like pattern on the front. Motifs reference nature, celestial symbols, and buffalo horns.

How to spot the real thing

- Run your fingers on the front—authentic pieces feel slightly raised.

- Turn it over—the back should look clean, not messy.

- Bands at the borders in red/black are common on traditional shawls.

What’s threatening it

Tourist-market knockoffs, machine embroidery, and the challenge of sustaining fair wages for time-intensive work. Commercialization brings income, but risks simplifying motifs or quality unless community control remains strong.

Who’s preserving it

Community organizations and NGOs (e.g., Keystone Foundation and partners behind the GI application) support training, quality standards, and market access while centering Toda cultural governance.

What it is

A square ikat scarf traditionally dyed in red, black, and white. “Telia” means “oily”—yarns are pre-treated with oil/alkaline baths for depth and fastness before the painstaking ikat (resist) dyeing. Historically exported to Gulf traders; now rare outside a few clusters. The GI Registry lists “Telia Rumal” (Telangana) as a registered GI.

How it’s made

Cotton yarns are repeatedly oiled and washed (a key step that gives Telia its name), then resist-bound and dyed so the design sits in the yarns themselves; when woven, the motifs emerge crisply on both sides.

How to spot the real thing

- Motifs are visible on both sides (true ikat).

- Palette typically sticks to red/black/white with geometric checks or temple forms.

- Handloom selvedges; soft handle from oiling and finishing.

What’s threatening it

Loss of traditional oiling know-how, solvent-based shortcuts, and printed look-alikes eroding prices. A few master weavers (notably award-winning revivalists) keep standards alive, but supply is tight.

Who’s preserving it

State handloom bodies and craft organizations have pushed GI, documentation, and exhibitions to re-introduce Telia to urban buyers.

Chanderi (Chanderi, Madhya Pradesh)

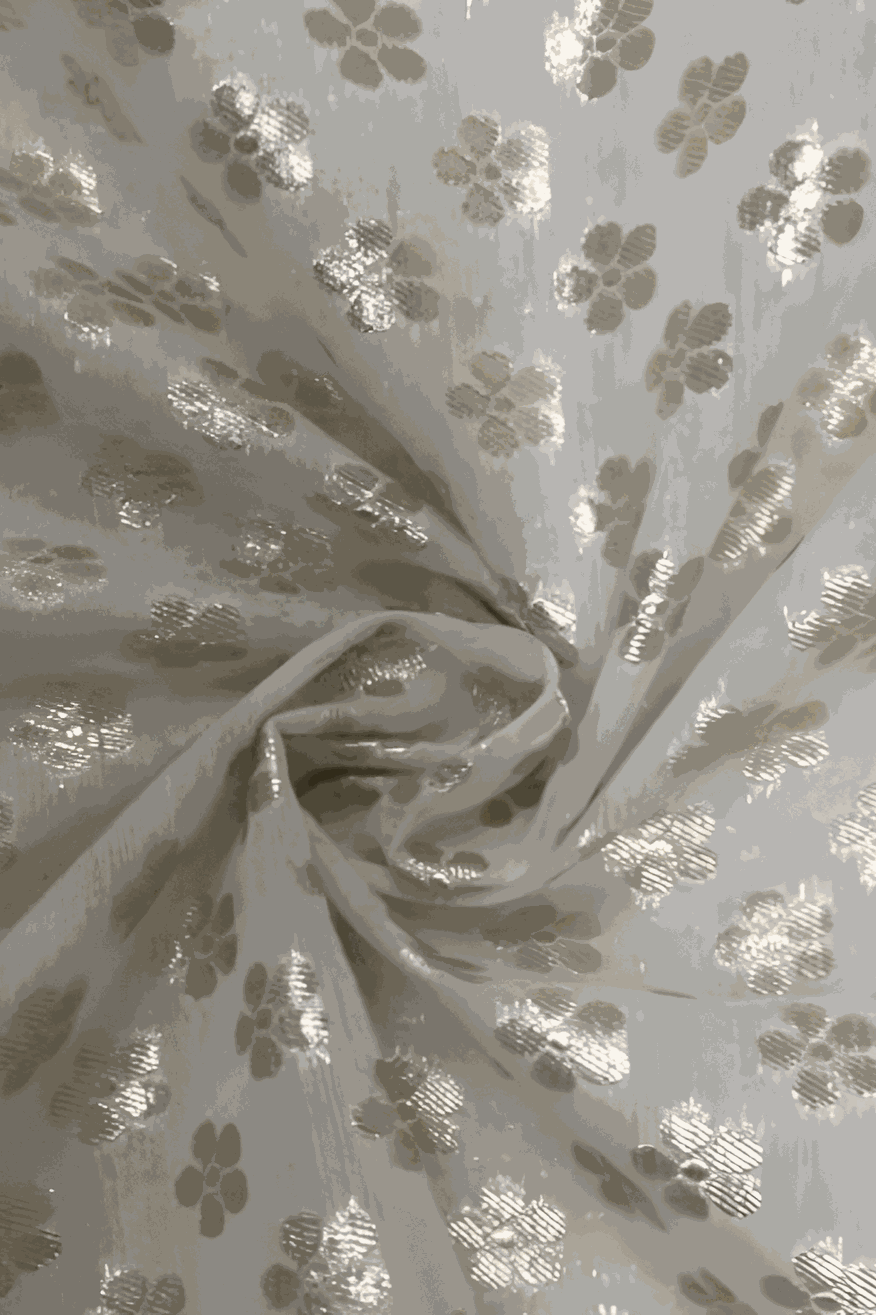

What it is

A sheer, airy handloom fabric (silk, cotton, or silk-cotton) famed for its gentle lustre and tiny woven butis. It’s a living classic—still woven at scale—but handloom segments face pressure from powerloom imitations. Chanderi sarees were among India’s earliest GIs (registered April 2, 2004).

How it’s made

Fine warps and wefts are hand-woven, often with zari in extra-weft to build tiny motifs; the cloth is semi-transparent, light, and soft. Government tourism and handloom sources profile Chanderi as a heritage weave of MP.

How to spot the real thing

- Hold it up to light: handloom Chanderi looks sheer but not flimsy.

- Butis have a slightly “placed” handfeel from extra-weft.

- Ask for GI/Handloom Mark where available (see below).

What’s threatening it

Cheaper powerloom “Chanderi-look” materials, inconsistent wages for complex work, and design dilution. Digital initiatives (like the Chanderiyaan project) and designer tie-ups have helped expand market access without abandoning hand techniques.